XALKORI Hard capsule Ref.[7200] Active ingredients: Crizotinib

Source: European Medicines Agency (EU) Revision Year: 2024 Publisher: Pfizer Europe MA EEIG, Boulevard de la Plaine 17, 1050 Bruxelles, Belgium

Pharmacodynamic properties

Pharmacotherapeutic group: Anti-neoplastic agents, protein kinase inhibitors

ATC code: L01ED01

Mechanism of action

Crizotinib is a selective small-molecule inhibitor of the ALK receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) and its oncogenic variants (i.e. ALK fusion events and selected ALK mutations). Crizotinib is also an inhibitor of the Hepatocyte Growth Factor Receptor (HGFR, c-Met) RTK, ROS1 (c-ros) and Recepteur d’Origine Nantais (RON) RTK. Crizotinib demonstrated concentration-dependent inhibition of the kinase activity of ALK, ROS1, and c-Met in biochemical assays and inhibited phosphorylation and modulated kinase-dependent phenotypes in cell-based assays. Crizotinib demonstrated potent and selective growth inhibitory activity and induced apoptosis in tumour cell lines exhibiting ALK fusion events (including echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 [EML4]-ALK and nucleophosmin [NPM]-ALK), ROS1 fusion events, or exhibiting amplification of the ALK or MET gene locus. Crizotinib demonstrated antitumour efficacy, including marked cytoreductive antitumour activity, in mice bearing tumour xenografts that expressed ALK fusion proteins. The antitumour efficacy of crizotinib was dose-dependent and correlated to pharmacodynamic inhibition of phosphorylation of ALK fusion proteins (including EML4-ALK and NPM-ALK) in tumours in vivo. Crizotinib also demonstrated marked antitumour activity in mouse xenograft studies, where tumours were generated using a panel of NIH-3T3 cell lines engineered to express key ROS1 fusions identified in human tumours. The antitumour efficacy of crizotinib was dose-dependent and demonstrated a correlation with inhibition of ROS1 phosphorylation in vivo. In vitro studies in 2 ALCL-derived cell lines (SU-DHL-1 and Karpas-299, both containing NPM-ALK) showed that crizotinib was able to induce apoptosis, and in Karpas-299 cells, crizotinib inhibited proliferation and ALK-mediated signaling at clinically achievable doses. In vivo data obtained in a Karpas-299 model showed complete regression of the tumour at a dose of 100 mg/kg once daily.

Clinical studies

Previously untreated ALK-positive advanced NSCLC – randomised Phase 3 Study 1014

The efficacy and safety of crizotinib for the treatment of patients with ALK-positive metastatic NSCLC, who had not received previous systemic treatment for advanced disease, were demonstrated in a global, randomised, open-label Study 1014.

The full analysis population included 343 patients with ALK-positive advanced NSCLC as identified by Fluorescence In Situ Hybridisation (FISH) prior to randomisation: 172 patients were randomised to crizotinib and 171 patients were randomised to chemotherapy (pemetrexed + carboplatin or cisplatin; up to 6 cycles of treatment). The demographic and disease characteristics of the overall study population were 62% female, median age of 53 years, baseline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0 or 1 (95%), 51% White and 46% Asian, 4% current smokers, 32% past smokers and 64% never smokers. The disease characteristics of the overall study population were metastatic disease in 98% of patients, 92% of patients' tumours were classified as adenocarcinoma histology and 27% of patients had brain metastases.

Patients could continue crizotinib treatment beyond the time of Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST)-defined disease progression at the discretion of the investigator if the patient was still experiencing clinical benefit. Sixty-five of 89 (73%) patients treated with crizotinib and 11 of 132 (8.3%) patients treated with chemotherapy continued treatment for at least 3 weeks after objective disease progression. Patients randomised to chemotherapy could cross over to receive crizotinib upon RECIST-defined disease progression confirmed by independent radiology review (IRR). One hundred forty-four (84%) patients in the chemotherapy arm received subsequent crizotinib treatment.

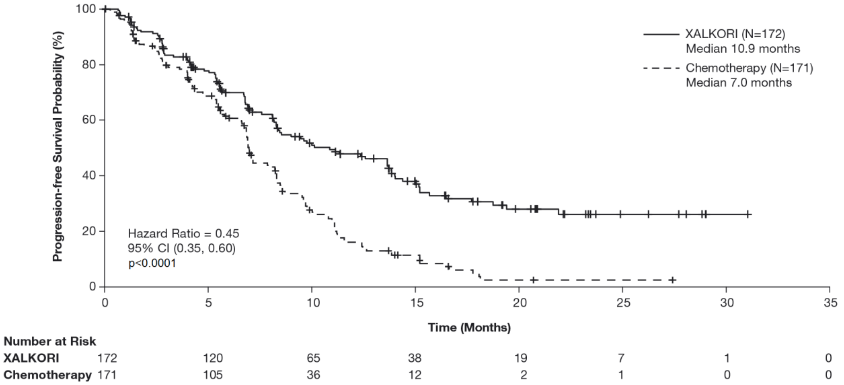

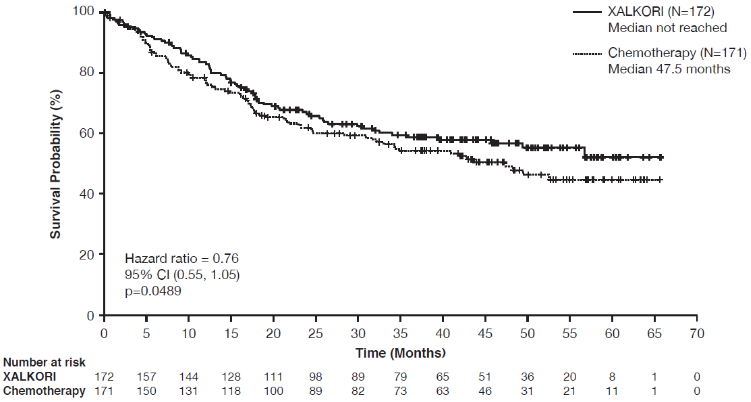

Crizotinib significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS), the primary objective of the study, compared to chemotherapy as assessed by IRR. The PFS benefit of crizotinib was consistent across subgroups of baseline patient characteristics such as age, gender, race, smoking class, time since diagnosis, ECOG performance status and presence of brain metastases. There was a numerical improvement in overall survival (OS) in the patients treated with crizotinib, although this improvement was not statistically significant. Efficacy data from randomised Phase 3 Study 1014 are summarised in Table 11, and the Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS and OS are shown in Figure 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 11. Efficacy results from randomised Phase 3 Study 1014 (full analysis population) in patients with previously untreated ALK-positive advanced NSCLC*:

| Response parameter | Crizotinib N=172 | Chemotherapy N=171 |

|---|---|---|

| Progression-free survival (based on IRR) | ||

| Number with event, n (%) | 100 (58%) | 137 (80%) |

| Median PFS in months (95% CI) | 10.9 (8.3, 13.9) | 7.0a (6.8, 8.2) |

| HR (95% CI)b | 0.45 (0.35, 0.60) | |

| p-valuec | <0.0001 | |

| Overall survivald | ||

| Number of deaths, n (%) | 71 (41%) | 81 (47%) |

| Median OS in months (95% CI) | NR (45.8, NR) | 47.5 (32.2, NR) |

| HR (95% CI)b | 0.76 (0.55, 1.05) | |

| p-valuec | 0.0489 | |

| 12-Month survival probability,d % (95% CI) | 83.5 (77.0, 88.3) | 78.4 (71.3, 83.9) |

| 18-Month survival probability,d % (95% CI) | 71.5 (64.0, 77.7) | 66.6 (58.8, 73.2) |

| 48-Month survival probability,d % (95% CI) | 56.6 (48.3, 64.1) | 49.1 (40.5, 57.1) |

| Objective response rate (based on IRR) | ||

| Objective response rate % (95% CI) | 74% (67, 81) | 45%e (37, 53) |

| p-valuef | <0.0001 | |

| Duration of response | ||

| Monthsg (95% CI) | 11.3 (8.1, 13.8) | 5.3 (4.1, 5.8) |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio; IRR=independent radiology review; N/n=number of patients; NR=not reached; PFS=progression-free survival; ORR=objective response rate; OS=overall survival.

* PFS, Objective Response Rate and Duration of Response are based on the data cutoff date of 30 November 2013; OS is based on the last patient last visit date of 30 November 2016, and is based on a median follow up of approximately 46 months.

a Median PFS times were 6.9 months (95% CI: 6.6, 8.3) for pemetrexed/cisplatin (HR=0.49; p-value <0.0001 for crizotinib compared with pemetrexed/cisplatin) and 7.0 months (95% CI: 5.9, 8.3) for pemetrexed/carboplatin (HR=0.45; p-value <0.0001 for crizotinib compared with pemetrexed/carboplatin).

b Based on the Cox proportional hazards stratified analysis.

c Based on the stratified log-rank test (1-sided).

d Updated based on final OS analysis. OS analysis was not adjusted for the potentially confounding effects of cross over (144 [84%] patients in the chemotherapy arm received subsequent crizotinib treatment).

e ORRs were 47% (95% CI: 37, 58) for pemetrexed/cisplatin (p-value <0.0001 compared with crizotinib) and 44% (95% CI: 32, 55) for pemetrexed/carboplatin (p-value <0.0001 compared with crizotinib).

f Based on the stratified Cochran-Mantel--Haenszel test (2-sided).

g Estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier curves for progression-free survival (based on IRR) by treatment arm in randomised Phase 3 Study 1014 (full analysis population) in patients with previously untreated ALK-positive advanced NSCLC:

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; N=number of patients; p=p-value.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival by treatment arm in randomised Phase 3 Study 1014 (full analysis population) in patients with previously untreated ALK-positive advanced NSCLC:

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; N=number of patients; p=p-value.

For patients with previously treated baseline brain metastases, the median intracranial time to progression (IC-TTP) was 15.7 months in the crizotinib arm (N=39) and 12.5 months in the chemotherapy arm (N=40) (HR=0.45 [95% CI: 0.19, 1.07]; 1-sided p-value=0.0315). For patients without baseline brain metastases, the median IC-TTP was not reached in either the crizotinib (N=132) or the chemotherapy arms (N=131) (HR=0.69 [95% CI: 0.33, 1.45]; 1-sided p-value=0.1617).

Patient-reported symptoms and global QOL were collected using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and its lung cancer module (EORTC QLQ-LC13). A total of 166 patients in the crizotinib arm and 163 patients in the chemotherapy arm had completed the EORTC QLQ-C30 and LC13 questionnaires at baseline and at least 1 postbaseline visit. Significantly greater improvement in global QOL was observed in the crizotinib arm compared to the chemotherapy arm (overall difference in change from baseline scores 13.8; p-value <0.0001).

Time to Deterioration (TTD) was prespecified as the first occurrence of a ≥10-point increase in scores from baseline in symptoms of pain in chest, cough or dyspnoea as assessed by EORTC QLQ-LC13.

Crizotinib resulted in symptom benefits by significantly prolonging TTD compared to chemotherapy (median 2.1 months versus 0.5 months; HR=0.59; 95% CI: 0.45, 0.77; Hochberg-adjusted log-rank 2-sided p-value =0.0005).

Previously treated ALK-positive advanced NSCLC – randomised Phase 3 Study 1007

The efficacy and safety of crizotinib for the treatment of patients with ALK-positive metastatic NSCLC, who had received previous systemic treatment for advanced disease, were demonstrated in a global, randomised, open-label Study 1007.

The full analysis population included 347 patients with ALK-positive advanced NSCLC as identified by FISH prior to randomisation. One hundred seventy-three (173) patients were randomised to crizotinib, and 174 patients were randomised to chemotherapy (either pemetrexed or docetaxel). The demographic and disease characteristics of the overall study population were 56% female, median age of 50 years, baseline ECOG performance status 0 (39%) or 1 (52%), 52% White and 45% Asian, 4% current smokers, 33% past smokers and 63% never smokers, 93% metastatic and 93% of patients' tumours were classified as adenocarcinoma histology.

Patients could continue treatment as assigned beyond the time of RECIST-defined disease progression at the discretion of the investigator if the patient was perceived to be experiencing clinical benefit. Fifty-eight of 84 (69%) patients treated with crizotinib and 17 of 119 (14%) patients treated with chemotherapy continued treatment for at least 3 weeks after objective disease progression. Patients randomised to chemotherapy could crossover to receive crizotinib upon RECIST-defined disease progression confirmed by IRR.

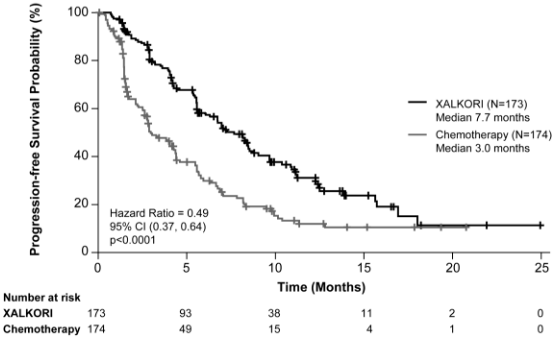

Crizotinib significantly prolonged PFS, the primary objective of the study, compared to chemotherapy as assessed by IRR. The PFS benefit of crizotinib was consistent across subgroups of baseline patient characteristics such as age, gender, race, smoking class, time since diagnosis, ECOG performance status, presence of brain metastases and prior EGFR TKI therapy.

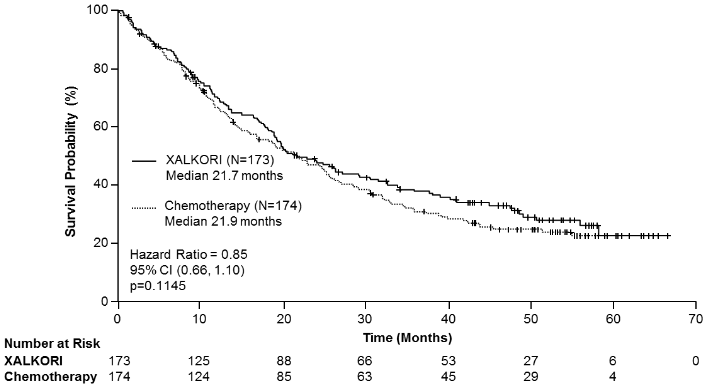

Efficacy data from Study 1007 are summarised in Table 12, and the Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS and OS are shown in Figures 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 12. Efficacy results from randomised Phase 3 Study 1007 (full analysis population) in patients with previously treated ALK-positive advanced NSCLC*:

| Response Parameter | Crizotinib N=173 | Chemotherapy N=174 |

|---|---|---|

| Progression-free survival (based on IRR) | ||

| Number with event, n (%) | 100 (58%) | 127 (73%) |

| Type of event, n (%) | ||

| Progressive disease | 84 (49%) | 119 (68%) |

| Death without objective progression | 16 (9%) | 8 (5%) |

| Median PFS in months (95% CI) | 7.7 (6.0, 8.8) | 3.0a (2.6, 4.3) |

| HR (95% CI)b | 0.49 (0.37, 0.64) | |

| p-valuec | <0.0001 | |

| Overall survivald | ||

| Number of deaths, n (%) | 116 (67%) | 126 (72%) |

| Median OS in months (95% CI) | 21.7 (18.9, 30.5) | 21.9 (16.8, 26.0) |

| HR (95% CI)b | 0.85 (0.66, 1.10) | |

| p-valuec | 0.1145 | |

| 6-Month survival probability,e % (95% CI) | 86.6 (80.5, 90.9) | 83.8 (77.4, 88.5) |

| 1-Year survival probability,e % (95% CI) | 70.4 (62.9, 76.7) | 66.7 (59.1, 73.2) |

| Objective response rate (based on IRR) | ||

| Objective response rate % (95% CI) | 65% (58, 72) | 20%f (14, 26) |

| p-valueg | <0.0001 | |

| Duration of response | ||

| Mediane, months (95% CI) | 7.4 (6.1, 9.7) | 5.6 (3.4, 8.3) |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio; IRR=independent radiology review; N/n=number of patients; PFS=progression-free survival; ORR=objective response rate; OS=overall survival.

* PFS, objective response rate and duration of response are based on the data cutoff date of 30 March 2012; OS is based on the data cutoff date of 31 August 2015.

a The median PFS times were 4.2 months (95% CI: 2.8, 5.7) for pemetrexed (HR=0.59; p-value=0.0004 for crizotinib compared with pemetrexed) and 2.6 months (95% CI: 1.6, 4.0) for docetaxel (HR=0.30; p-value <0.0001 for crizotinib compared with docetaxel).

b Based on the Cox proportional hazards stratified analysis.

c Based on the stratified log-rank test (1-sided).

d Updated based on final OS analysis. Final OS analysis was not adjusted for the potentially confounding effects of crossover (154 [89%] patients received subsequent crizotinib treatment).

e Estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

f ORRs were 29% (95% CI: 21, 39) for pemetrexed (p-value <0.0001 compared with crizotinib) and 7% (95% CI: 2, 16) for docetaxel (p-value <0.0001 compared with crizotinib).

g Based on the stratified Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test (2-sided).

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier curves for progression-free survival (based on IRR) by treatment arm in randomised Phase 3 Study 1007 (full analysis population) in patients with previously treated ALK-positive advanced NSCLC:

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival by treatment arm in randomised Phase 3 Study 1007 (full analysis population) in patients with previously treated ALK-positive advanced NSCLC:

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; N=number of patients; p=p-value.

Fifty-two (52) patients treated with crizotinib and 57 chemotherapy-treated patients with previously treated or untreated asymptomatic brain metastases were enrolled in randomised Phase 3 Study 1007. Intracranial Disease Control Rate (IC-DCR) at 12 weeks was 65% and 46% for crizotinib and chemotherapy-treated patients, respectively.

Patient-reported symptoms and global QOL were collected using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and its lung cancer module (EORTC QLQ-LC13) at baseline (Day 1 Cycle 1) and Day 1 of each subsequent treatment cycle. A total of 162 patients in the crizotinib arm and 151 patients in the chemotherapy arm had completed the EORTC QLQ-C30 and LC13 questionnaires at baseline and at least 1 postbaseline visit.

Crizotinib resulted in symptoms benefit by significantly prolonging time to deterioration (median 4.5 months versus 1.4 months) in patients who reported symptoms of pain in chest, dyspnoea or cough, compared to chemotherapy (HR 0.50; 95% CI: 0.37, 0.66; Hochberg-adjusted log-rank p<0.0001).

Crizotinib showed a significantly greater improvement from baseline compared to chemotherapy in alopecia (Cycles 2 to 15; p-value <0.05), cough (Cycles 2 to 20; p-value <0.0001), dyspnoea (Cycles 2 to 20; p-value <0.0001), haemoptysis (Cycles 2 to 20; p-value <0.05), pain in arm or shoulder (Cycles 2 to 20; p-value <0.0001), pain in chest (Cycles 2 to 20; p-value <0.0001) and pain in other parts (Cycles 2 to 20; p-value <0.05). Crizotinib resulted in a significantly lower deterioration from baseline in peripheral neuropathy (Cycles 6 to 20; p-value <0.05), dysphagia (Cycles 5 to 11; p-value <0.05) and sore mouth (Cycle 2 to 20; p-value <0.05) compared to chemotherapy.

Crizotinib resulted in overall global quality of life benefits with a significantly greater improvement from baseline observed in the crizotinib arm compared to the chemotherapy arm (Cycles 2 to 20; p-value <0.05).

Single-arm studies in ALK-positive advanced NSCLC

The use of single-agent crizotinib in the treatment of ALK-positive advanced NSCLC was investigated in 2 multinational, single-arm studies (Studies 1001 and 1005). Of the patients enrolled in these studies, the patients described below had received prior systemic therapy for locally advanced or metastatic disease. The primary efficacy endpoint in both studies was objective response rate (ORR) according to RECIST.

A total of 149 ALK-positive advanced NSCLC patients, including 125 patients with previously treated ALK-positive advanced NSCLC, were enrolled into Study 1001 at the time of data cutoff for PFS and ORR analysis. The demographic and disease characteristics were 50% female, median age of 51 years, baseline ECOG performance status of 0 (32%) or 1 (55%), 61% White and 30% Asian, less than 1% were current smokers, 27% former smokers, 72% never smokers, 94% metastatic and 98% of the cancers were classified as adenocarcinoma histology. The median duration of treatment was 42 weeks.

A total of 934 patients with ALK-positive advanced NSCLC were treated with crizotinib in Study 1005 at the time of data cutoff for PFS and ORR analysis. The demographic and disease characteristics were 57% female, median age of 53 years, baseline ECOG performance status of 0/1 (82%) or ⅔ (18%), 52% White and 44% Asian, 4% current smokers, 30% former smokers, 66% never smokers, 92% metastatic and 94% of the cancers were classified as adenocarcinoma histology. The median duration of treatment for these patients was 23 weeks. Patients could continue treatment beyond the time of RECIST-defined disease progression at the discretion of the investigator. Seventy-seven of 106 patients (73%) continued crizotinib treatment for at least 3 weeks after objective disease progression.

Efficacy data from Studies 1001 and 1005 are provided in Table 13.

Table 13. ALK-positive advanced NSCLC efficacy results from Studies 1001 and 1005:

| Efficacy parameter | Study 1001 | Study 1005 |

|---|---|---|

| N=125a | N=765a | |

| Objective response rateb [% (95% CI)] | 60 (51, 69) | 48 (44, 51) |

| Time to tumour response [median (range)] weeks | 7.9 (2.1, 39.6) | 6.1 (3, 49) |

| Duration of responsec [median (95% CI)] weeks | 48.1 (35.7, 64.1) | 47.3 (36, 54) |

| Progression-free survivalc [median (95% CI)] months | 9.2 (7.3, 12.7) | 7.8 (6.9, 9.5)d |

| N=154e | N=905e | |

| Number of deaths, n (%) | 83 (54%) | 504 (56%) |

| Overall survivalc [median (95% CI)] months | 28.9 (21.1, 40.1) | 21.5 (19.3, 23.6) |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; N/n=number of patients; PFS=progression-free survival.

a Per data cutoff dates 01 June 2011 (Study 1001) and 15 February 2012 (Study 1005).

b Three patients were not evaluable for response in Study 1001, and 42 patients were not evaluable for response in Study 1005.

c Estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

d PFS data from Study 1005 included 807 patients in the safety analysis population who were identified by the FISH assay (data cutoff date 15 February 2012).

e Per data cutoff date 30 November 2013.

OS1-positive advanced NSCLC

The use of single-agent crizotinib in the treatment of ROS1-positive advanced NSCLC was investigated in multicenter, multinational, single-arm Study 1001. A total of 53 ROS1-positive advanced NSCLC patients were enrolled in the study at the time of data cutoff, including 46 patients with previously treated ROS1-positive advanced NSCLC and a limited number of patients (N=7) who had no prior systemic treatment. The primary efficacy endpoint was ORR according to RECIST. Secondary endpoints included time to tumour response (TTR), duration of response (DoR), PFS and OS. Patients received crizotinib 250 mg orally twice daily.

The demographic characteristics were 57% female; median age 55 years; baseline ECOG performance status of 0 or 1 (98%) or 2 (2%); 57% White and 40% Asian; 25% former smokers and 75% never smokers. The disease characteristics were 94% metastatic, 96% adenocarcinoma histology and 13% with no prior systemic therapy for metastatic disease.

In Study 1001, patients were required to have advanced ROS1-positive advanced NSCLC prior to entering the clinical study. For most patients, ROS1-positive NSCLC was identified by FISH. The median duration of treatment was 22.4 months (95% CI: 15.0, 35.9). There were 6 complete responses and 32 partial responses for an ORR of 72% (95% CI: 58%, 83%). The median DoR was 24.7 months (95% CI: 15.2, 45.3). Fifty percent of objective tumour responses were achieved during the first 8 weeks of treatment. The median PFS at the time of data cutoff was 19.3 months (95% CI: 15.2, 39.1). The median OS at the time of data cutoff was 51.4 months (95% CI: 29.3, NR).

Efficacy data from ROS1-positive advanced NSCLC patients from Study 1001 are provided in Table 14.

Table 14. ROS1-positive advanced NSCLC efficacy results from Study 1001:

| Efficacy parameter | Study 1001 N=53a |

|---|---|

| Objective response rate [% (95% CI)] | 72 (58, 83) |

| Time to tumour response [median (range)] weeks | 8 (4, 104) |

| Duration of responseb [median (95% CI)] months | 24.7 (15.2, 45.3) |

| Progression-free survivalb [median (95% CI)] months | 19.3 (15.2, 39.1) |

| OSb [median (95% CI)] months | 51.4 (29.3, NR) |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; N=number of patients; NR=not reached; OS=overall survival.

OS is based on a median follow up of approximately 63 months.

a Per data cutoff date 30 June 2018.

b Estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Non-adenocarcinoma histology

Twenty-one patients with previously untreated and 12 patients with previously treated advanced ALK-positive non-adenocarcinoma histology NSCLC were enrolled in randomised Phase 3 Studies 1014 and 1007, respectively. The subgroups in these studies were too small to draw reliable conclusions. Of note, no patients with SCC histology were randomised in the crizotinib arm in Study 1007 and no patients with SCC were enrolled in Study 1014 due to pemetrexed-based regimen being used as a comparator.

Information is available from 45 response-evaluable patients with previously treated non-adenocarcinoma NSCLC (including 22 patients with SCC) in Study 1005. Partial responses were observed in 20 of 45 patients with non-adenocarcinoma NSCLC for an ORR of 44%, and 9 of 22 patients with SCC NSCLC for an ORR of 41%, both of which were less than the ORR reported in Study 1005 (54%) for all patients.

Re-treatment with crizotinib

No safety and efficacy data are available on re-treatment with crizotinib of patients who received crizotinib in previous lines of therapy.

Elderly

Of 171 ALK-positive NSCLC patients treated with crizotinib in randomised Phase 3 Study 1014, 22 (13%) were 65 years or older, and of 109 ALK-positive patients treated with crizotinib who crossed over from chemotherapy arm, 26 (24%) were 65 years or older. Of 172 ALK-positive patients treated with crizotinib in randomised Phase 3 Study 1007, 27 (16%) were 65 years or older. Of 154 and 1063 ALK-positive NSCLC patients in single arm Studies 1001 and 1005, 22 (14%) and 173 (16%) were 65 years or older, respectively. In ALK-positive NSCLC patients, the frequency of adverse reactions was generally similar for patients <65 years of age and patients ≥65 years of age with the exception of oedema and constipation, which were reported with greater frequency (≥15% difference) in Study 1014 among patients treated with crizotinib ≥65 years of age. No patients in the crizotinib arm of randomised Phase 3 Studies 1007 and 1014, and single-arm Study 1005 were >85 years. There was one ALK-positive patient >85 years old out of 154 patients in single-arm Study 1001 (see also sections 4.2 and 5.2). Of the 53 ROS1-positive NSCLC patients in single-arm Study 1001, 15 (28%) were 65 years or older. There were no ROS1-positive patients >85 years old in Study 1001.

Paediatric population

The safety and efficacy of crizotinib have been established in paediatric patients with relapsed or refractory systemic ALK-positive ALCL from 3 to <18 years of age or with unresectable, recurrent, or refractory ALK-positive IMT from 2 to <18 years of age (see sections 4.2 and 4.8). There are no safety or efficacy data of crizotinib treatment in ALK-positive ALCL paediatric patients below 3 years of age or ALK-positive IMT paediatric patients below 2 years of age.

Paediatric patients with ALK-Positive ALCL (see sections 4.2 and 5.2)

The use of single-agent crizotinib in the treatment of paediatric patients with relapsed or refractory systemic ALK-positive ALCL was investigated in Study 0912 (n=22). All patients enrolled had received prior systemic treatment for their disease: 14 had 1 prior line of systemic treatment, 6 had 2 prior lines of systemic treatment and 2 had more than 2 prior lines of systemic treatment. Of the 22 patients enrolled in Study 0912, 2 had received a prior bone marrow transplant. No clinical data are currently available on paediatric patients who undergo hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) following treatment with crizotinib. Patients with primary or metastatic central nervous system (CNS) tumours were excluded from the study. The 22 patients enrolled in Study 0912 received a starting dose of crizotinib at 280 mg/m² (16 patients) or 165 mg/m² (6 patients) twice daily. Efficacy endpoints from Study 0912 included ORR, TTR and DoR per independent review. The median follow-up time was 5.5 months.

The demographic characteristics were 23% female; median age 11 years; 50% White and 9% Asian. Baseline performance status as measured by Lansky Play Score (patients ≤16 years) or Karnofsky Performance Score (patients >16 years) was 100 (50% of patients) or 90 (27% of patients). Patient enrollment by age was 4 patients from 3 to <6 years, 11 patients from 6 to <12 years and 7 patients from 12 to <18 years. No patients below 3 years of age were enrolled in the study.

Efficacy data as assessed by independent review are provided in Table 15.

Table 15. Systemic ALK-positive ALCL efficacy results from Study 0912:

| Efficacy Parametera | N=22b |

|---|---|

| ORR, [% (95% CI)]c Complete response, n (%) Partial response, n (%) | 86 (67, 95) 17 (77) 2 (9) |

| TTRd Median (range) months | 0.9 (0.8, 2.1) |

| DoRd,e Median (range) months | 3.6 (0.0, 15.0) |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; DoR=duration of response; N/n=number of patients; ORR=objective response rate; TTR=time to tumour response.

a As assessed by Independent Review Committee using Lugano Classification response criteria.

b Per data cutoff date 19 Jan 2018.

c 95% CI based on Wilson score method.

d Estimated using descriptive statistics.

e Ten of the 19 (53%) patients proceeded to hematopoietic stem cell transplant after occurrence of an objective response. DoR for patients who underwent transplant was censored at the time of their last tumour assessment prior to transplant.

Paediatric patients with ALK-Positive IMT (see sections 4.2 and 5.2)

The use of single-agent crizotinib in the treatment of paediatric patients with unresectable, recurrent, or refractory ALK-positive IMT was investigated in Study 0912 (n=14). Most patients (12 out of 14) enrolled had received surgery (8 patients) or prior systemic treatment (7 patients: 5 had 1 prior line of systemic treatment, 1 had 2 prior lines of systemic treatment and 1 had more than 2 prior lines of systemic treatment) for their disease. Patients with primary or metastatic CNS tumours were excluded from the study. The 14 patients enrolled in Study 0912 received a starting dose of crizotinib at 280 mg/m² (12 patients), 165 mg/m² (1 patient) or 100 mg/m² (1 patient) twice daily. Efficacy endpoints for Study 0912 included ORR, TTR and DoR per independent review. The median follow-up time was 17.6 months.

The demographic characteristics were 64% female; median age 6.5 years; 71% White. Baseline performance status as measured by Lansky Play Score (patients ≤16 years) or Karnofsky Performance Score (patients >16 years) was 100 (71% of patients), 90 (14% of patients) or 80 (14% of patients). Patient enrollment by age was 4 patients from 2 to <6 years, 8 patients from 6 to <12 years and 2 patients from 12 to <18 years. No patients below 2 years of age were enrolled in the study.

Efficacy data as assessed by independent review are provided in Table 16.

Table 16. ALK-positive IMT efficacy results from Study 0912:

| Efficacy Parametera | N=14b |

|---|---|

| ORR, [% (95% CI)]c Complete response, n (%) Partial response, n (%) | 86 (60, 96) 5 (36) 7 (50) |

| TTRd Median (range) months | 1.0 (0.8, 4.6) |

| DoRd,e Median (range) months | 14.8 (2.8, 48.9) |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; DoR=duration of response; N/n=number of patients; ORR=objective response rate; TTR=time to tumour response.

a As assessed by Independent Review Committee.

b Per data cutoff date 19 Jan 2018.

c 95% CI based on Wilson score method.

d Estimated using descriptive statistics.

e None of the 12 patients with objective tumour response had follow-up disease progression, and their DoR was censored at the time of the last tumour assessment.

Paediatric patients with ALK-positive or ROS1-positive NSCLC

The European Medicines Agency has waived the obligation to submit the results of studies with XALKORI in all subsets of the paediatric population in NSCLC (see section 4.2 for information on paediatric use).

Pharmacokinetic properties

Pharmacokinetic properties of crizotinib were characterised in adults unless otherwise specifically indicated in paediatric patients.

Absorption

XALKORI 200 mg and 250 mg hard capsules

Following oral single-dose administration in the fasted state, crizotinib is absorbed with median time to achieve peak concentrations of 4 to 6 hours. With twice daily dosing, steady-state was achieved within 15 days. The absolute bioavailability of crizotinib was determined to be 43% following the administration of a single 250 mg oral dose.

A high-fat meal reduced crizotinib AUCinf and Cmax by approximately 14% when a 250 mg single dose was given to healthy volunteers. Crizotinib can be administered with or without food (see section 4.2).

XALKORI granules in capsules for opening

Following oral single-dose administration in the fasted state, the crizotinib granules in capsules for opening are bioequivalent to crizotinib capsules.

The crizotinib oral granules in capsules for opening administered with a high-fat/high-calorie meal reduced crizotinib AUCinf and Cmax by approximately 15% and 23%, respectively, compared to the same formulation administered under fasted conditions. Crizotinib granules in capsules for opening can be administered with or without food (see section 4.2).

Distribution

The geometric mean volume of distribution (Vss) of crizotinib was 1772 L following intravenous administration of a 50 mg dose, indicating extensive distribution into tissues from the plasma.

Binding of crizotinib to human plasma proteins in vitro is 91% and is independent of medicinal product concentration. In vitro studies suggest that crizotinib is a substrate for P-glycoprotein (P-gp).

Biotransformation

In vitro studies demonstrated that CYP3A4/5 were the major enzymes involved in the metabolic clearance of crizotinib. The primary metabolic pathways in humans were oxidation of the piperidine ring to crizotinib lactam and O-dealkylation, with subsequent Phase 2 conjugation of O-dealkylated metabolites.

In vitro studies in human liver microsomes demonstrated that crizotinib is a time-dependent inhibitor of CYP2B6 and CYP3A (see section 4.5). In vitro studies indicated that clinical drug-drug interactions are unlikely to occur as a result of crizotinib-mediated inhibition of the metabolism of medicinal products that are substrates for CYP1A2, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19 or CYP2D6.

In vitro studies showed that crizotinib is a weak inhibitor of UGT1A1 and UGT2B7 (see section 4.5). However, in vitro studies indicated that clinical drug-drug interactions are unlikely to occur as a result of crizotinib-mediated inhibition of the metabolism of medicinal products that are substrates for UGT1A4, UGT1A6 or UGT1A9.

In vitro studies in human hepatocytes indicated that clinical drug-drug interactions are unlikely to occur as a result of crizotinib-mediated induction of the metabolism of medicinal products that are substrates for CYP1A2.

Elimination

Following single doses of crizotinib, the apparent plasma terminal half-life of crizotinib was 42 hours in patients.

Following the administration of a single 250 mg radiolabelled crizotinib dose to healthy subjects, 63% and 22% of the administered dose was recovered in faeces and urine, respectively. Unchanged crizotinib represented approximately 53% and 2.3% of the administered dose in faeces and urine, respectively.

Coadministration with medicinal products that are substrates of transporters

Crizotinib is an inhibitor of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) in vitro. Therefore, crizotinib may have the potential to increase plasma concentrations of coadministered medicinal products that are substrates of P-gp (see section 4.5).

Crizotinib is an inhibitor of OCT1 and OCT2 in vitro. Therefore, crizotinib may have the potential to increase plasma concentrations of coadministered medicinal products that are substrates of OCT1 or OCT2 (see section 4.5).

In vitro, crizotinib did not inhibit the human hepatic uptake transport proteins organic anion transporting polypeptide (OATP)1B1 or OATP1B3 or the renal uptake transport proteins organic anion transporter (OAT)1 or OAT3 at clinically relevant concentrations. Therefore, clinical drug-drug interactions are unlikely to occur as a result of crizotinib-mediated inhibition of the hepatic or renal uptake of medicinal products that are substrates for these transporters.

Effect on other transport proteins

In vitro, crizotinib is not an inhibitor of Bile Salt Export Pump (BSEP) at clinically relevant concentrations.

Pharmacokinetics in special patient groups

Hepatic impairment

Crizotinib is extensively metabolised in the liver. Patients with mild (either AST >ULN and total bilirubin ≤ULN or any AST and total bilirubin >ULN but ≤1.5 × ULN), moderate (any AST and total bilirubin >1.5 × ULN and ≤3 × ULN), or severe (any AST and total bilirubin >3 × ULN) hepatic impairment or normal (AST and total bilirubin ≤ULN) hepatic function, who were matched controls for mild or moderate hepatic impairment, were enrolled in an open-label, non-randomised clinical study (Study 1012), based on NCI classification.

Following crizotinib 250 mg twice daily dosing, patients with mild hepatic impairment (N=10) showed similar systemic crizotinib exposure at steady state compared to patients with normal hepatic function (N=8), with geometric mean ratios for area under the plasma concentration-time curve as daily exposure at steady state (AUCdaily) and Cmax of 91.1% and 91.2%, respectively. No starting dose adjustment is recommended for patients with mild hepatic impairment.

Following crizotinib 200 mg twice daily dosing, patients with moderate hepatic impairment (N=8) showed higher systemic crizotinib exposure compared to patients with normal hepatic function (N=9) at the same dose level, with geometric mean ratios for AUCdaily and Cmax of 150% and 144%, respectively. However, the systemic crizotinib exposure in patients with moderate hepatic impairment at the dose of 200 mg twice daily was comparable to that observed from patients with normal hepatic function at a dose of 250 mg twice daily, with geometric mean ratios for AUCdaily and Cmax of 114% and 109%, respectively.

The systemic crizotinib exposure parameters AUCdaily and Cmax in patients with severe hepatic impairment (N=6) receiving a crizotinib dose of 250 mg once daily were approximately 64.7% and 72.6%, respectively, of those from patients with normal hepatic function receiving a dose of 250 mg twice daily.

An adjustment of the dose of crizotinib is recommended when administering crizotinib to patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment (see sections 4.2 and 4.4).

Renal impairment

Patients with mild (60 ≤CLcr <90 mL/min) and moderate (30 ≤CLcr <60 mL/min) renal impairment were enrolled in single-arm Studies 1001 and 1005. The effect of renal function as measured by baseline CLcr on observed crizotinib steady-state trough concentrations (Ctrough,ss) was evaluated. In Study 1001, the adjusted geometric mean of plasma Ctrough,ss in mild (N=35) and moderate (N=8) renal impairment patients were 5.1% and 11% higher, respectively, than those in patients with normal renal function. In Study 1005, the adjusted geometric mean Ctrough,ss of crizotinib in mild (N=191) and moderate (N=65) renal impairment groups were 9.1% and 15% higher, respectively, than those in patients with normal renal function. In addition, the population pharmacokinetic analysis using data from Studies 1001, 1005 and 1007 indicated CLcr did not have a clinically meaningful effect on the pharmacokinetics of crizotinib. Due to the small size of the increases in crizotinib exposure (5%-15%), no starting dose adjustment is recommended for patients with mild or moderate renal impairment.

After a single 250 mg dose in subjects with severe renal impairment (CLcr <30 mL/min) not requiring peritoneal dialysis or haemodialysis, crizotinib AUCinf and Cmax increased by 79% and 34%, respectively, compared to those with normal renal function. An adjustment of the dose of crizotinib is recommended when administering crizotinib to patients with severe renal impairment not requiring peritoneal dialysis or haemodialysis (see sections 4.2 and 4.4).

Paediatric population for cancer patients

At a dosing regimen of 280 mg/m² twice daily (approximately 2 times the recommended adult dose), observed crizotinib predose concentration (Ctrough) at steady state is similar regardless of body weight quartiles. The observed mean Ctrough at steady state in paediatric patients at 280 mg/m² twice daily is 482 ng/mL, while observed mean Ctrough at steady state in adult cancer patients at 250 mg twice daily across different clinical studies ranged from 263 to 316 ng/mL.

In paediatric patients, body weight has a significant effect on the pharmacokinetics of crizotinib with lower crizotinib exposures observed in patients with higher body weight.

Age

Based on the population pharmacokinetic analysis of adult data from Studies 1001, 1005 and 1007, age has no effect on crizotinib pharmacokinetics (see sections 4.2 and 5.1).

Body weight and gender

Based on the population pharmacokinetic analysis of adult data from Studies 1001, 1005 and 1007, there was no clinically meaningful effect of body weight or gender on crizotinib pharmacokinetics.

Ethnicity

Based on the population pharmacokinetic analysis of data from Studies 1001, 1005 and 1007, the predicted area under the plasma concentration-time curve at steady-state (AUCss) (95% CI) was 23%-37% higher in Asian patients (N=523) than in non-Asian patients (N=691).

In studies in patients with ALK-positive advanced NSCLC (N=1669), the following adverse reactions were reported with an absolute difference of ≥10% in Asian patients (N=753) than in non-Asian patients (N=916): elevated transaminases, decreased appetite, neutropenia and leukopenia. No adverse drug reactions were reported with an absolute difference of ≥15%.

Geriatric

Limited data are available in this subgroup of patients (see sections 4.2 and 5.1). Based on the population pharmacokinetic analysis of data in Studies 1001, 1005 and 1007, age has no effect on crizotinib pharmacokinetics.

Cardiac electrophysiology

The QT interval prolongation potential of crizotinib was assessed in patients with either ALK-positive or ROS1-positive NSCLC who received crizotinib 250 mg twice daily. Serial ECGs in triplicate were collected following a single dose and at steady state to evaluate the effect of crizotinib on QT intervals. Thirty-four of 1619 patients (2.1%) with at least 1 postbaseline ECG assessment were found to have QTcF ≥500 msec, and 79 of 1585 patients (5.0%) with a baseline and at least 1 postbaseline ECG assessment had an increase from baseline QTcF ≥60 msec by automated machine-read evaluation of ECG (see section 4.4).

An ECG substudy using blinded manual ECG measurements was conducted in 52 ALK-positive NSCLC patients who received crizotinib 250 mg twice daily. Eleven (21%) patients had an increase from Baseline in QTcF value ≥30 to <60 msec and 1 (2%) patient had an increase from Baseline in QTcF value of ≥60 msec. No patients had a maximum QTcF ≥480 msec. The central tendency analysis indicated that all upper limits of the 90% CI for the LS mean change from Baseline in QTcF at all Cycle 2 Day 1 time points were <20 msec. A pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis suggested a relationship between crizotinib plasma concentration and QTc. In addition, a decrease in heart rate was found to be associated with increasing crizotinib plasma concentration (see section 4.4), with a maximum mean reduction of 17.8 beats per minute (bpm) after 8 hours on Cycle 2 Day 1.

Preclinical safety data

In rat and dog repeat-dose toxicity studies up to 3-month duration, the primary target organ effects were related to the gastrointestinal (emesis, faecal changes, congestion), haematopoietic (bone marrow hypocellularity), cardiovascular (mixed ion channel blocker, decreased heart rate and blood pressure, increased LVEDP, QRS and PR intervals and decreased myocardial contractility) or reproductive (testicular pachytene spermatocyte degeneration, single-cell necrosis of ovarian follicles) systems. The No Observed Adverse Effect Levels (NOAEL) for these findings were either subtherapeutic or up to 1.3-fold human clinical exposure based on AUC. Other findings included an effect on the liver (elevation of liver transaminases) and retinal function, and potential for phospholipidosis in multiple organs without correlative toxicities.

Crizotinib was not mutagenic in vitro in the bacterial reverse mutation (Ames) assay. Crizotinib was aneugenic in an in vitro micronucleus assay in Chinese Hamster Ovary cells and in an in vitro human lymphocyte chromosome aberration assay. Small increases of structural chromosomal aberrations at cytotoxic concentrations were seen in human lymphocytes. The No Observed Effect Levels (NOEL) for aneugenicity was approximately 1.8- to 2.1-fold human clinical exposure based on AUC.

Carcinogenicity studies with crizotinib have not been performed.

No specific studies with crizotinib have been conducted in animals to evaluate the effect on fertility; however, crizotinib is considered to have the potential to impair reproductive function and fertility in humans based on findings in repeat-dose toxicity studies in the rat. Findings observed in the male reproductive tract included testicular pachytene spermatocyte degeneration in rats given ≥50 mg/kg/day for 28 days (approximately 1.1- to 1.3-fold human clinical exposure based on AUC).

Findings observed in the female reproductive tract included single-cell necrosis of ovarian follicles of a rat given 500 mg/kg/day for 3 days.

Crizotinib was not shown to be teratogenic in pregnant rats or rabbits. Post-implantation loss was increased at doses ≥50 mg/kg/day (approximately 0.4 to 0.5 times the AUC at the recommended human dose) in rats, and reduced foetal body weights were considered adverse effects in the rat and rabbit at 200 and 60 mg/kg/day, respectively (approximately 1.2- to 2.0-fold human clinical exposure based on AUC).

Decreased bone formation in growing long bones was observed in immature rats at 150 mg/kg/day following once daily dosing for 28 days (approximately 3.3 to 3.9 times human clinical exposure based on AUC). Other toxicities of potential concern to paediatric patients have not been evaluated in juvenile animals.

The results of an in vitro phototoxicity study demonstrated that crizotinib may have phototoxic potential.

© All content on this website, including data entry, data processing, decision support tools, "RxReasoner" logo and graphics, is the intellectual property of RxReasoner and is protected by copyright laws. Unauthorized reproduction or distribution of any part of this content without explicit written permission from RxReasoner is strictly prohibited. Any third-party content used on this site is acknowledged and utilized under fair use principles.